The evolution of CONSOL Energy’s Harvey complex has been long and winding, but with a successful integration now complete, a favorable future awaits

By Donna Schmidt, Field Editor

CONSOL Energy has historically been known to the industry as a colossus, owner of a massive collection of reserves locked within one of the nation’s most lush coal seams. It was a longwall leader. However, goals change, paths divert, ideas evolve, and — especially true in the coal scene — the market ebbs and flows. Change means adjustment, but it also can mean growth for the better. Such is the case with what is now known as the Harvey mine, at the heart of CONSOL’s Pennsylvania operations in the extreme southwestern corner of the state.

In 1984 and 1990, respectively, two of the company’s flagship mines — sister operations Bailey and Enlow Fork — began producing coal from their respective sections and, ultimately, their longwalls. Time passed, more areas were mined out and sealed, and operations continued. Today, both are considered among the top producing U.S. mines.

But original plans years ago didn’t call for the Harvey mine, or anything like it, really. How did it come to be and why? CONSOL Energy Senior Vice President of Pennsylvania operations Chuck Shaynak recently revealed the history and development that have brought the mine to where it is now.

Harvey Mine: Just the Facts

- Continuous miner development began: 2009

- Longwall operations began: 2014

- Current production via: 1 longwall, 4 CM sections

- 2014 production: 3.2 million tons

- Annual production capacity (ave.): 5.5 million tons

HISTORY: EVOLUTION OF BAILEY, ENLOW FORK, AND HARVEY

Tucked into the area between Waynesburg and Washington, Pennsylvania, and Morgantown and Wheeling, West Virginia, sits a far-reaching complex amidst what exemplifies Northern Appalachia — mountain foothills with four distinct seasons (sometimes more than one in the same day) and a population that has been toiling in the region’s coal mines for generations.

Before Bailey and Enlow came to be in their current forms, CONSOL collected numerous reserves in the area as far back as 1965, when the company bought 262 million clean tons within the Nineveh reserve. By 1977, it had added 209 million tons from the Manor reserve as well. They were followed by Alexander, with 93 million tons, just across the state line in West Virginia’s panhandle (1981), and then it went north into Washington County, Pennsylvania, with the acquisition of the 174-million-ton Berkshire reserve (1985).

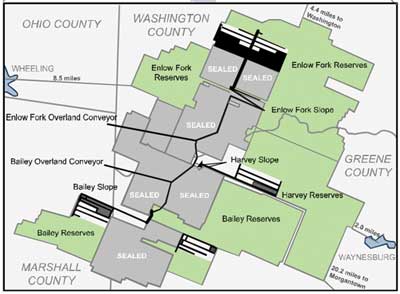

A map of the footprint made by Bailey, Enlow Fork and Harvey in the southwestern Pennsylvania foothills.

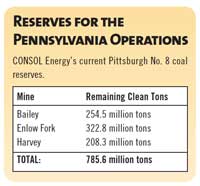

A map of the footprint made by Bailey, Enlow Fork and Harvey in the southwestern Pennsylvania foothills.Chevron and Penn Central, with 92 million tons, was acquired by the company in 1993, and two years later, it would take over the Greene Hill reserve to the west of Waynesburg. Between 1996 and 2015, it finished its series of contiguous takeovers with 57 million tons from the Mine 84 reserve and the 151-million-ton Drummond reserve. The enviable portfolio totaled 1.25 billion clean tons, and CONSOL has so far mined less than half of it at 472 million tons.

According to Shaynak, today’s Bailey/Enlow Fork/Harvey campus is not what engineers anticipated all of those decades ago; originally, there were to be five short-lived operations with a new mine coming online every several years. That was 1980, and construction began at Bailey the following year; by 1982, crews were constructing a shaft, slope and railroad spur to ready for a connection of the shaft and slope bottom in 1984. The first longwall panel started in 1985, measuring 600 feet in width and 7,000 ft in length; a second longwall began in 1986, and the 1A panel clocked in at 750 ft wide and 8,700 ft long.

At the same time, Enlow Fork was also being shaped. Work on the shaft and slope began in 1983, though due to the market the mine was put on hold for about seven years. Fast forward to 1990, and three entries were developed off of the Bailey slope bottom. Its first longwall panel, at 750 ft wide and 9,000 ft long, cut first coal in 1991, and a second longwall began the following year with a similar-sized panel.

Both Bailey and Enlow Fork, as part of that initial growth plan, grew older, and as the years passed officials started to see deterioration in belts and tracks so discussions began on how to progress in mining the remaining reserves. Initial plans in 1984 included connecting the two mines, which were now running at prime production with their longwall pairs, to make for what would be a literal combined future.

It was then that CONSOL opted to move forward with both Bailey and Enlow Fork and bring on a third mine at some point in the future. That would be done by putting in slopes for both mines with new overland conveyor infrastructure to what would become a combined capacity plant (see more on the plant history and operations on page 36).

“We couldn’t keep going with same infrastructure because of the age of the entries,” Shaynak said. “We hadn’t planned for it,” adding that high costs meant the initial plan was “out of the question” when there was a mine already in existence.

“The original plan for the third mine was an Enlow Fork expansion, extend to the north, move out to the east,” he said. “That would have required a new refuse plant, rail spur, and a lot of additional costs.”

Because there was room to increase that capacity on the Bailey side, CONSOL again adapted to the situation by progressing with a plan to expand with a new mine off the bottom of Enlow Fork’s reserves.

The main area of concern then became timing — with a vastly changed outlook for the mines’ future, the timelines for slopes and other crucial components became priority.

“Obviously, to get to the reserve the quickest, most productive [way] was to do development off of Bailey’s bottom. Our final decision was to keep Enlow mining to the north [and] bring Harvey off Bailey’s bottom to get eastern reserves. It was the quickest and lowest cost and best for timing,” he said.

THE 30-YEAR PROJECT

With a new and very long-term future in its sights, CONSOL began looking at how to grow the complex along with the big plans it had ahead of it. Work began in 2008 on those steps toward adding Harvey, then called the BMX mine, beginning with a sealing project to separate the Bailey mine from the new operation. A total of 34 seals of various types were installed, including five solid block layers and three Micon block layers with an overall thickness of 7.2 ft. Crews overcame some areas of cave as well as a need to keep Bailey’s south section open where coal was still being cut. The west area, while abandoned, was also left open for a time as examinations were still required and ventilation was still in place. Other changes included 30,000 ft (5.8 miles) of main line haulage ground control and development to the portal and floor-to-roof supports in main line haulage cross cuts on the Harvey side using 40-ton RocProps.

Additionally, mesh was added to roof and ribs, and a 15-ft-wide channel was installed on the roof for support with five bolts across, cable bolts in the center and two bolts on the outside of either side.

Continuous miner development commenced in January 2009, and crews had their work cut out for them in terms of development, particularly with planned average longwall panel dimensions of 1,500 ft wide by 15,000 ft long, supported by 262 shields.

“It was developed with one crew, three shifts per day,” Shaynak said. “When they got out to the bleeder system, we added more crews: crews to drive the tailgate, crews to drive the headgate. One unique thing…because of distance and to get 7 North developed and running quick, we mined it in a reverse direction. At same time, we continued to develop 7 North for the long haul.”

In the meantime, work began on the surface for Harvey’s future as well, beginning with needed upgrades for storage and transport. CONSOL was able to store 135,000 tons of clean (165,000 raw tons), or about two days of production, on-site with all enclosed storage. Additionally, changes to a 14.7-mile rail spur from Waynesburg to the plant (owned by the company, maintained by CSX) was outlined in the plan, including a new dual-batch train loadout facility with a 9,000-ton-per-hour (tph) capacity and 8,000 ft of new rail siding.

“With the new side track, they would have the ability to have one train loading and another two staged and ready.

Perhaps the biggest needed improvement to the surface facilities was the preparation plant, which required increased capacity to manage all three operations. When the initial plan was in place and Bailey was producing, coal was stockpiled on-site for six months as its supporting prep plant was erected.

HARVEY MINE OF TODAY — AND TOMORROW

Before the operation was officially dedicated on June 24, 2014, at the Patterson Creek portal and its name changed to the Harvey mine, both underground and surface crews were getting into a production rhythm and ramping up to full production. The 1A East longwall panel was mined while the mains development was still ongoing, and the panel was completed just three weeks before the ceremony. The 2A longwall commenced work two weeks later.

Once the Patterson Creek portal was finally complete, the mine was ready for its unveiling, and the Bailey BMX expansion became formally known as the Harvey mine for longtime CONSOL executive J. Brett Harvey. “He was really instrumental in everything seen here today,” Shaynak said of the complex. “Safety for the industry and the company. His legacy will be able to live on for a long time.”

The longwall dimensions had the distinction of being the longest in company history, a record the operation still holds. It mines the 5-ft main seam bench with a Cat armored face conveyor and stageloader and a Joy shearer.

UNDERGROUND TRAINING CENTER One of the additions made to Harvey and the overall complex for its long-term future is also a first for the industry — an underground miner training academy within the underground workings. Located just off Bailey’s bottom reserves, where crews first began to create today’s Harvey mine, the center is the only truly underground facility of its kind in the nation where miners can train on an actual section and with real equipment, not simulators.

One of the additions made to Harvey and the overall complex for its long-term future is also a first for the industry — an underground miner training academy within the underground workings. Located just off Bailey’s bottom reserves, where crews first began to create today’s Harvey mine, the center is the only truly underground facility of its kind in the nation where miners can train on an actual section and with real equipment, not simulators.

The academy has a staff of five, including two foremen and three hourly trainers. It contains two classrooms as well as the CM action center that encompasses an entire equipment fleet. Some of the education held to date has included roof bolting, rerailing, shivving and foreman training. More classes are currently being developed.

CENTRALIZED PLANT

Another major change needed to bring the entire complex to where it is now, and where it is headed over the coming decades, was a centralized preparation plant. A one-circuit facility began operations in 1984, and became two circuits once a second plant came online with the start of the Enlow Fork mine in 1991. Eight years later in 1999, following the growth of longwall faces, equipment upgrades and other efficiency improvements, there was a need to increase the capacity; that would happen again in 2004, but for a decade after, it remained the same.

Along came Harvey, and the game would once again change for CONSOL officials. Two final upgrades would bring the plant (which now includes, in chronological order, Modules 1A, 2A, 2B, 1B and 2C) from 940 tph in 1984 to a staggering 8,200 tph by 2013 when the upgrades were completed. Today, there are two separate plants, each with its own feed belt. Plant 1 has two circuits, and Plant 2 has three, allowing for all to be run together or for progress without bottlenecking in the event any one circuit needs repairs or maintenance.

“Coal is drawn from the silos from each mine and blended by sulfur by each mine. As it comes out, it is put into separate clean coal silos,” Shaynak noted. “As drawn out from there, can be blended again for sulfur. All we blend for is sulfur — as little as possible [as], at times, it can reduce efficiencies.”

There are a total of six raw coal silos surrounding the plants, including two each for Enlow Fork and Bailey and the newest for Harvey. A project currently under way by CONSOL crews is the dissembling and replacement of the plant’s original refuse belts.

Note: This is an adaptation of a presentation given at the Longwall USA event held during June by CONSOL Energy Senior Vice President of Pennsylvania operations Chuck Shaynak.