Just four days into the new year, less than a week after the coal industry marked its safest year in history for 2015 with 11 fatalities, any positive momentum that had been accumulated with the record was turned on its ear with the first coal-mining death of 2016.

As it turns out, that was just the beginning. Compounding the bad start was another fatality just 12 days later, and a third three days after that. In all, four deaths beset coal in the first quarter, all of them underground and all of them contained to three Eastern states.

Two of the miners lost were killed in accidents classified by the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) as Fall of Rib. The remaining two were classified Powered Haulage and Machinery. While trends at this point are more difficult to isolate, one alarming connection can be made: three of the four victims had five years or less of experience at the mine site where they died and five years or less at the job or task they were assigned.

All of that said, there is no reason to believe that, as an industry, coal cannot beat its own record this year, keeping in mind that the first quarter of last year also began with a group of four fatalities. This optimism rings particularly true if the lessons from the below events can be applied, along with those in history, to prevent the loss of life moving forward.

Fatality 1 — Lower War Eagle

The first coal mining death, recorded on January 4, was the result of a powered haulage accident at Greenbrier Minerals’ Lower War Eagle operation in Cyclone, Wyoming County, West Virginia.

Shortly after midnight, while preparing to change out a hold-up roller as he was conducting belt maintenance, 53-year-old belt foreman and fireboss Peter Sprouse was fatally injured when he became entangled in a moving belt conveyor at the No. 1 belt drive.

While Sprouse had more than 34 years of mining experience, only four-and-a-half years of that was for Lower War Eagle, which is owned by Coronado Coal. About 50 workers were in the mine at the time.

In a fatalgram released shortly after, MSHA officials stressed in its best practices that no work should ever be performed on a moving conveyor belt, and that no person should ever enter a clearance-restricted area along a moving belt.

Additionally, before any work is done to a belt, a visual disconnect should be done to ensure power is off, along with one’s own lock and tag. All machinery should be blocked against motion before maintenance or repairs begin.

A final investigation report on Sprouse’s death is still pending.

Fatality 2 — Dana Mining 4 West

On January 16 in southwestern Pennsylvania, a rib roll incident killed 31-year-old continuous miner (CM) operator Jeremy Neice at Dana Mining Co. of Pennsylvania’s 4 West mine in Greene County, just north of the Mason-Dixon Line. The 12-year mining veteran was pinned beneath a coal/rock rib 4.5 ft in length, 3 ft high and 3 ft in thickness while he was operating a miner unit at the No. 2 entry. He had been at the mine, working as a CM operator, for a little more than two weeks.

While the release of a final investigation report is also still pending for this incident, MSHA’s fatalgram with preliminary findings stressed the importance of thorough roof, rib, and face examinations for all areas where crews will be working and traveling. It also urged mines to know and follow their approved roof control plan and incorporate extra support as needed in areas with roof or rib abnormalities.

Other best practices issued by the agency included awareness of potential hazards at all times; additional safety precautions as mining heights increase in order to prevent development of rib hazards; and the avoidance of areas of close clearance between ribs and equipment.

Operators should ensure they are installing rib bolts with adequate surface coverage hardware on cycle and in a consistent pattern, MSHA added, and setting post on 4-ft centers along questionable rib lines. Meanwhile, miners are encouraged to be alert for changing conditions, scale or support from a safe location, and to cord off hazardous areas until issues can be addressed.

Dana Mining’s parent company is GenPower Holdings.

Fatality 3 — Dotiki

Just hours later, back in Kentucky, a 36-year-old continuous miner operator was fatally injured after being crushed between his CM and the rib at Alliance resource Partners’ Dotiki mine, operated by affiliate Webster County Coal.

Just hours later, back in Kentucky, a 36-year-old continuous miner operator was fatally injured after being crushed between his CM and the rib at Alliance resource Partners’ Dotiki mine, operated by affiliate Webster County Coal.

In that incident, Nathan Phillips, who had five years in the mining industry and at the mine, but only a little more than one year operating a CM, was pinned between the tail of the unit and the inby rib as it was being positioned to cut the No. 6 left. There were 124 individuals working in the mine at the time of the accident.

MSHA’s fatalgram, issued shortly after Phillips’ death, indicated that the victim had been positioning the trailing cable, and trammed the machine into the last open cross-cut between the No. 6 and No. 5 entries.

Avoiding “red zone” areas was the spotlight of the agency’s best practices, with investigators stressing the importance of staying out of the zones when operating a machine or doing other work in the vicinity of a CM. It went on to urge maintaining a safe distance from any moving equipment, as well as positioning the CM boom away from the operator and other workers during the unit’s movement.

Other suggestions for safer working included ensuring the proper working order of the proximity detection system, and awareness that radio frequency interference and the electromagnetic interference generated by mining electrical systems can disrupt communications between miner wearable components (MWCs) and the proximity system.

“MWCs should be worn securely at all times, according to manufacturer recommendations and in a manner so that warning lights and sounds can be seen and heard,” MSHA officials said.

Investigators also asked operations to make sure that continuous mining machine pump motors are disabled before handling trailing cables, and never to defeat machine safety controls.

Once again, at press time, the final investigation report on the incident was pending.

Just after the third fatality, MSHA Assistant Secretary of Mine Safety and Health Joseph Main called the string of events “troubling” for the coal community.

“In light of declining coal market conditions, we all need to be mindful that effective safety and health protections that safeguard our nation’s coal miners need to be in place every day at every mine in the country,” he said, adding that the agency was planning to ramp up its targeted enforcement in light of the emerging trend.

He also said federal officials would be boosting its outreach to emphasize “the need for continued vigilance in miner safety and health.”

Fatality 4 — Huff Creek No. 1

The first quarter of the year was just a few days from concluding when word came of the fourth coal death of 2016, which is also the most recent one for the year (as of press time). Also in Kentucky, the fall of rib incident took 48-year-old miner operator Mark Frazier.

The first quarter of the year was just a few days from concluding when word came of the fourth coal death of 2016, which is also the most recent one for the year (as of press time). Also in Kentucky, the fall of rib incident took 48-year-old miner operator Mark Frazier.

The March 25 incident occurred at Arch Coal’s Lone Mountain Processing Huff Creek No. 1 mine in Holmes Mill, Harlan County. There is not yet any information on the amount of rib material that fell onto Frazier while he was at the mine’s B-3 Mains coal transportation borehole construction site.

The victim was a 30-year mining veteran; he had about 14.5 years of experience at the mine and about 7.5 as a miner operator.

Of the 105 employees at Huff Creek, six were in the mine at the time of the accident.

MSHA has not yet released its fatalgram report with best practices for accident prevention. Its final report is also still pending.

Incorrect Mine Door Installation Cause of PA Death

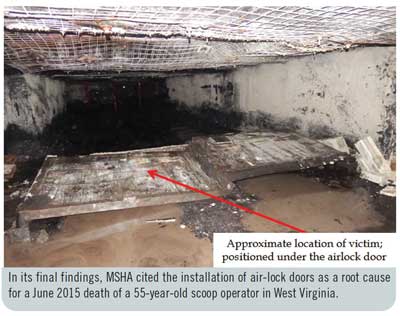

On February 25, federal investigators released its final findings from a review of the June 27, 2015, accident — once again at Dana Mining of Pennsylvania’s 4 West operation in Greene County — that killed a 55-year-old scoop operator.

Outby diesel scoop operator John (Bill) Kelly was passing through an area of the mine just before midnight when he opened a set of air-lock doors, then shut them behind him. As one set of the doors closed, both they and the frame dislodged from their installation point and fell onto him.

“Kelly…opened both sets of air-lock doors located at the 63.5 and 64.5 cross-cuts and then trammed the diesel scoop and supply wagons to a point where the last supply wagon was inby the inby set of air-lock doors,” MSHA said in the 20-page report. “[He] then traveled on foot to close the outby set of air-lock doors prior to closing the inby set. While closing the outby set of air-lock doors, [they] and frame fell on Kelly, pinning him to the mine floor.”

The victim, who was unresponsive when found, was carried about 6,700 ft to the escape elevator and taken to the surface following CPR attempts. He was pronounced dead about 90 minutes post-accident at the South West Regional Medical Center in neighboring Waynesburg.

Federal officials said that each set of air-lock doors measured 14 ft wide and 5.5 ft high. Combined, all components of the door weighed a total of 980 lb. The two door sets involved in the incident were installed about 85 ft apart, and their placement had been completed just five days prior.

As for why Kelly had opened both sets of doors, MSHA determined that, as he was operating a train of equipment measuring 96 ft, it would not fit into the 85 ft length between the air locks.

“Each set of…doors would see an incremental increase or decrease in external pressure across each set of doors as they were being opened or closed when used and installed properly,” officials said. “This sudden increase in external airflow pressure caused the outby set of air-lock doors to become dislodged due to not being properly installed per manufacturer’s recommendations.”

The investigating group were clear in their findings that it was “evident” that the doors had not been installed correctly, noting several issues, but added that the doors’ incorrect use by having two open at once only compounded the condition.

“There was mine sealant on the top of the two outside support columns, and five out of the six T-handle set screws were not installed in the lintels and columns. Without the required T-handle set screws, the air-lock doors would not be adequately secured,” the report stated. “The roof cleat was missing from the top of the left column (looking outby) of the outby set of air-lock doors. When the set of inby air-lock doors at the number 64.5 cross-cut was inspected, similar conditions were found.

“There was one T-handle set screw present in the left side of the air-lock lintel (looking outby) at the outby set of air-lock doors, and there was one T-handle set screw present in the left side of the air-lock column (looking outby) at the inby set of air-lock doors. Both T-handle set screws were not tightened.

“The manufacturer’s installation instructions require that a hydraulic jack be used to tighten the columns between the mine floor and roof to secure the frame in place; afterward, all T-handle set screws are to be secured very tight to anchor the air-lock doors in place.”

MSHA additionally found that the three miners tasked with the door installations less than a week prior had not been task trained on correct installation procedures.

It was that lack of training, along with incorrect installation, that was found to be the cause of the accident; Kelly’s incorrect use of the doors was also a contributory factor.

In its root cause analysis, federal investigators ordered the operator to develop a policy requiring all persons to install the mine’s ventilation controls, including air locks, in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions; that policy includes initial training, supervised instruction and documentation that training was completed.

Additionally, the mine trained its brattice men and masons post-accident on how to build all types of ventilation controls, including air locks, to manufacturer’s spec. This, too, includes training, supervised instruction and completion documentation. All workers were retrained all miners in the proper use and operation of air-lock doors as well.

The 4 West Mine received three significant and substantial (S&S) violations, two 104(d)s and one 104(a), as a result of the fatal accident.

One 104(d)(1) S&S citation cited 30 CFR Section 48.7(c) for the failure to train employees on safe work procedures. The second 104(d)(1) S&S order cited 30 CFR Section 75.333(d)(2) for a failure to install both pairs of air-lock doors to be of sufficient strength to serve their intended purpose of maintaining separation and permitting travel between or within air courses or entries. The single 104(a) S&S citation, for a violation of 30 CFR Section 75.333(d)(3), was issued due to the improper operation of the door sets.

Speed, Seat Belt Use at Core of Republic Energy Fatality

As Coal Age was going to press near the close of the year, MSHA issued its final investigation report for the March 17, 2015, powered haulage fatality at the Republic Energy complex in Fayette County, West Virginia.

In that incident, 52-year-old contract truck driver Von Bower was killed while driving a fuel truck on a mine haulage road.

According to the probe’s findings, the tandem axle truck, which was fully loaded with about 3,500 gallons of diesel fuel, was found on its top near the bottom of a long descending grade, which included a sharp curve to the right.

“The vehicle was found with the top of the cab crushed and both doors closed. Since there was no indication the truck traveled onto the berm or hillside, the driver likely made a sharp turn, at too high of a speed, to follow the road,” MSHA investigators said. “This indicates that the speed of the truck was not under control.”

There were no eyewitnesses to the accident, and no other injuries were involved.

In its interviews, the agency said it was not able to determine if Bower had been wearing a seat belt; while one person recalled seeing him without it, it was also thought that it could have been removed post-accident. An autopsy ruled that the victim’s death was an accident and not the result of natural causes, such as a heart attack during the truck’s operation.

A review of the physical factors of the accident, including the 1997 Kenworth W900 tractor he had been operating, was conducted as part of the probe; in that portion, it was determined that the truck was likely traveling at a speed exceeding 17 miles per hour when he overturned.

“The accident occurred because the contract truck driver was unable to maintain full control of his fully loaded fuel truck while descending a long, steep grade on a mine haul road,” MSHA concluded. “The…investigation determined that the truck was traveling at too high a rate of speed to allow it to negotiate a sharp curve near the bottom of the haul road, causing the fuel truck to overturn and skid to a stop on its top, fatally injuring the driver.”

It issued a 104(a) citation to contractor Rogers Petroleum Services for its violation of 30 CFR Section 77.1607(b) for failure to control.