WHAT CAN WE LEARN IN ORDER TO AVOID REPEATING THESE MISTAKES?

By Donna Schmidt, Field Editor

| The first death of the year occured January 16 at Mettiki Coal’s Mountain View operation in West Virginia. |

The initial quarter of 2014 ended with three coal mining-related deaths in the U.S., and on the surface, all of the events are different. As the industry continues its road to zero deaths, what can be taken from the three incidents to help prevent more of the same? Some examination of the details reveals a few similarities that may be significant in the effort to eliminate fatal injuries.

The first death of the year occurred January 16 at Mettiki Coal’s Mountain View operation in West Virginia, when general inside laborer Daniel Lambka, 20, was crushed when he was struck by a feeder.

According to federal investigators, Lambka was standing between the coal rib and the feeder when the securing post dislodged, allowing the tailpiece unit to shift and pin him between the rib and the frame of the feeder.

He had just finished connecting a chain between the feeder and the tailpiece when the accident occurred.

Lambka was fairly new to the industry, with just 2.5 years of experience. He had been at the Alliance Resource Partners-owned operation for a little more than four months.

While a final report on the miner’s death has so far not been released, the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) said in its initial findings of the underground powered haulage incident that other miners may prevent similar events by de-energizing and locking out conveyor belts before repositioning the tailpiece, and to use equipment and material that is capable of supporting that tailpiece.

Among its other recommendations was the establishment and discussion of safe work procedures before beginning any work, and the identification and control of all hazards associated with the work to be performed and the methods to properly protect persons.

The second death of the year occurred a little more than a month later in Virginia, when continuous miner operator Arthur Gelentser was killed in an underground machinery accident at SunCoke Energy’s Dominion No. 30 mine in Buchanan.

Once again, many factors of the situation were similar. The miner was, again, fairly young — just 24 — and had worked a little more than one year of his 5.5-year mining background at the complex.

Unlike the first fatality, Gelentser’s death was recorded at a much smaller operation with approximately 85 employees, but unfortunately, the details felt almost like an echo of January’s news.

“The second shift continuous miner operator was tramming the mining machine in the last open crosscut between the No. 2 entry and the No. 1 entry when he was caught between the remote control-operated continuous mining machine and the coal rib,” MSHA said in its preliminary report.

“The continuous miner operator received fatal crushing injuries.”

Federal officials are still conducting its final investigation of the event leading up to the miner’s death, but in its most recent findings of the incident, investigators stressed the use of proximity detection systems to protect crews underground. Along with that, all miners are encouraged to review, discuss and train often on red zone areas in the mine.

MSHA also asked operations to ensure they have developed policies and procedures for starting and tramming self-propelled equipment, especially remote-controlled continuous mining machines.

The third fatality in the first quarter of 2014 occurred March 25 in Indiana. Once again, the death was of an underground worker, and the victim had the least amount of experience of all three — just 23 weeks on the job.

|

| Continuous miner operator Arthur Gelenster was killed in an underground machinery accident at SunCoke Energy’s Dominion No. 30 mine in Buchanan, Virginia. |

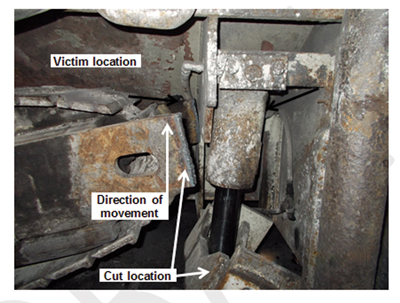

Mechanic trainee Timothy Memmer, 41, was working the owl shift at another Alliance Resource mine, Gibson County Coal’s Gibson complex, when he was killed in a machinery accident.

While working on an Auxier Welding belt feeder in the mine’s No. 4 working section, Memmer was cutting through the inner left-side side plate and, upon completion of the cut, the crawler frame pivoted upward and pinned the victim between the crawlers and frame of the feeder.

Just as in the first death, the mine was of a larger size with a payroll of 376, and the victim was one of 52 working on his shift.

In its preliminary report, MSHA investigators put the spotlight on equipment repair and blocking units against motion, including the control or release of stored energy in a piece of machinery before initiating repairs.

Additionally, the agency reminded operators to establish and discuss safe work procedures with crews before beginning work.

MSHA is still working on the final report for this incident as well.

|

| All three fatalities in the first quarter, including that of mechanic trainee Timothy Memmer, involved machinery in some manner. |

While one death is obviously one too many, three over the year’s first three months is already a better record than 2013, when there were six coal deaths through April of that year. However, in 2012, there was one coal fatality year-to-date through April, and two each in 2010 and 2011, respectively.

The total number of fatilities in coal for 2013 was 20, matching the year prior, and both were down from 21 in 2011.

With many months still to come in the balance of the year, the industry still has time to help prevent the situations that led to the deaths of these three workers. Communications between management and miners (and miners with their co-workers) is vital for any type of hazard protection, but judging from the three aforementioned fatalities, more dialogue may be needed on the interactions of pedestrians with mobile equipment underground.

Additionally, there is no substitute for proper job training with miners new to the industry or new to a specific job; this factor played a role in all three fatal accidents. From offering refresher training courses to opening lines of discussion on making a mine safer and better, the importance of ensuring every worker is confident in their tasks at hand cannot be substituted.