It goes without saying that 16 coal deaths is 16 too many. However, it also speaks to a safety culture that is, by and large, an industry-wide paradigm shift that continues to bear results with each day. Changing regulations aside, it is no longer acceptable to the U.S. mining community to log hundreds of fatal accidents, as was the case a century ago; knowledge and experience has brought about some of the best safety technology in any industrial trade and are unquestionably putting it to good use.

The Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), tasked with oversight of all accident data regardless of outcome, said in its recent preliminary release of figures that the most common mining accident causes in 2014 were powered haulage and machinery; five powered haulage and five machinery related deaths occurred in coal mines (powered haulage accounted for eight of the 24 deaths in metal and nonmetal mining).

The final quarter of the year was quite active for mining as a whole, with nine fatalities recorded, but it was steady versus previous periods in coal with four (more detailed information on those fatalities begins below).

As the new year has begun, the mood in mining safety can be classified most accurately as cautiously optimistic; while we set a new benchmark in modern worker safety for coal miners, the task now becomes maintaining that progress and keeping that motivation high.

“While MSHA and the mining industry have made a number of improvements and have been moving mine safety in the right direction, these deaths, particularly those in the metal and nonmetal industry, makes clear the need to do more to protect our nation’s miners,” said Assistant Secretary of Labor for Mine Safety and Health Joseph Main in late January. “Advancements in health and safety demand the cooperation of the entire mining community. Miners deserve the reassurance that they will return home safely and healthy after every shift.”

Part of taking the most from such unfortunate events is examining what occurred so that issues involved in each respective event can be prevented in the future. Trends emerge from some of this data; some details just leave more unanswered questions. There is likely no mine manager out there, however, that would not take back the heartbreaking death of a colleague if they could. Putting knowledge of these incidents to work for a safer shift tomorrow is the next best thing.

MORE YEAR-END DETAILS

Ten coal mining deaths occurred underground and six occurred at surface operations. Of those, nine and six were at coal operations, respectively.

Nearly no coal-rich state was exempt, though the Illinois Basin sustained the least impact from the deaths and West Virginia topped the list with four. All but one respective incident resulted in a single death; only victims four and five at Brody Mining’s No. 1 operation in West Virginia were classified as part of a multiple fatality.

Midyear versus second-half figures were relatively steady, though several months shared more than one death before the calendar page could turn. Only one operator (Peabody Energy) shared more than one coal incident resulting in a fatality; while months apart, both were at the same Wyoming surface operation. Ten of the 16 were in Appalachia or the Illinois Basin.

One event in 2014 was not initially classified as a mining fatality, though it was classified before the end of the calendar year. Recorded as the 16th victim of the year on December 22 was a male miner that drowned at the Law River Crown Hill Dock facility in West Virginia on April 18 (a final federal investigation report on the findings from that event is still pending).

A LOOK AT 4Q

As Coal Age has done regularly over the year, information has been compiled for each of the events along with the status of preliminary or final findings. In addition to the aforementioned recent classification by federal officials, four other incidents — three in the east and one in the western coalfields — took four miners’ lives.

The first, on October 7, occurred at Commonwealth Mining’s Tinsley Branch HWM 61 highwall mine in Kentucky.

According to preliminary findings, 31-year-old Justin Mize entered a highwall miner entry at the Bell County operation to retrieve the right side cutter head chain for the miner. About 37 ft into the 9.5-ft-wide entry, he was struck by a rock measuring 8 ft by 6 ft wide and 16 in. in thickness.

| Justin Mize was killed in October at Commonwealth Mining’s Tinsley Branch HWM 61 highwall mine in Kentucky. |

Mize, a 13-year veteran of mining, was extracted from the entry by his crew, then transported to a local hospital where he died from his injuries about five hours later.

MSHA has not yet released its final report, but in its fatalgram alert regarding the incident, it stressed staying out from under an unsupported roof.

The agency also noted that no worker should ever enter a hole mined with a highwall mining machine or auger without a specific, detailed and approved plan to do so. In that plan, operators should specify methods for equipment retrieval that do not expose miners to hazards and also train all miners.

Investigators also reminded all of the nation’s operations in a list of best practices that they need to know and follow the provisions of the established ground control plan and keep all equipment in proper working order by establishing and implementing maintenance schedules.

The second occurred just a handful of days later at Peabody Powder River’s North Antelope Rochelle operation in Wyoming. MSHA classified it as a powered haulage event.

|

| One of two fatalities this year at Peabody Powder River’s North Antelope Rochelle operation Wyoming killed contractor truck driver Darwin Reimer. |

In it, contractor truck driver Darwin Reimer, 51, was removing top soil ahead of the East Elk Pit at the Campbell County complex when he drove off a highwall, landing about 240 ft below.

The victim had five years of experience, but had worked at the Powder River Basin operation a little less than a year.

In its preliminary recommendations for accident prevention, federal investigators urged equipment operation that was consistent with conditions of the mine’s roadways, grades, clearance, visibility, traffic and the type of equipment in use.

While commonplace for many, it also focused on the importance of standard signage for workers indicating traffic rules, signals and warnings.

Adequate berm and barrier design and maintenance was another best practice point, along with training for all workers and monitoring activities by all employees to ensure all safe work practices are followed.

MSHA has not yet released its final findings for Reimer’s death.

About a month later on November 10, Red Bone Mining’s Crawdad No. 1 operation in West Virginia was the site for the 14th fatal event in coal.

Classified by federal officials as fall of roof or back, it involved section foreman and then-roof bolter Raymond Savage, 49.

|

| Red Bone Mining’s Crawdad No. 1 operation in West Virginia was the site for the 14th fatal event in coal, when Raymond Savage was struck in a roof fall. |

In a preliminary federal report, those probing the incident said that Savage was involved in a roof fall at the 2 North Section at the No. 2 entry of the Monongalia County operation. A review found that the rock measured 5 ft long by 3 ft wide by 13 in. at its thickest point.

“It fell inby the last row of support between the ATRS and the left rib,” MSHA said. While a transport was made to the local hospital, the report listed the event date and time of death as the same point.

Investigators are still looking at the details of the event, and thus a final report was not available at press time. However, in its fatalgram alert posted by the agency to help prevent future similar incidents, MSHA stressed visual examinations of the roof, face and ribs, and immediately before any work is done in an area.

“Be alert to changing conditions, especially after activities that could cause roof disturbance,” it said in its best practices.

“While under supported roof, perform sound and vibration tests where roof supports are to be installed [and] adequately support or scale down any loose roof or rib material from a safe location.”

While an ATRS was in use in this case, the agency highlighted the need for all units on bolters to be maintained in good working condition and set firmly against the mine roof before supports are installed.

Additionally, all operations must ensure ATRS are set within 5 ft of permanent support as well as within 5 ft of the rib line. Additionally, all operators should stay under the roof bolting machine canopy when working in the area between the ATRS and the last row of permanent roof support.

It also focused its recommendations on the compliance to an approved roof control plan.

Experience was not an issue in the Red Bone incident; Savage had 27 years of experience and nearly 20 of that at the bituminous complex.

Finally, just weeks before the Christmas holiday, one final event — an underground powered haulage accident — took a Kentucky miner at the now-closed Highland Mining Highland 9 operation.

|

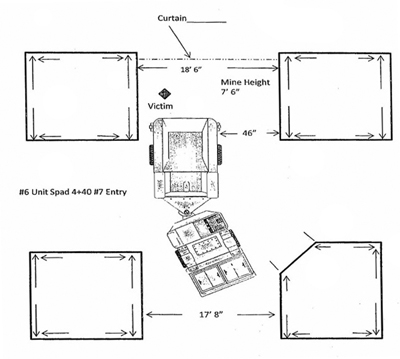

| The last 2014 fatal incident occurred at Highland Mining’s Highland 9 operation in Kentucky and took the life of Eli Eldridge, who was struck by a battery ram car. |

Repairman Eli Eldridge, 34, was struck by a battery ram car that was en route to a continuous miner in the No. 7 entry. The victim, a 15-year mining veteran, had been at the Union County complex just 36 weeks.

Some additional information was released shortly after when MSHA released its fatalgram. In it, investigators indicated that unit was traveling toward the face area, striking the victim with the left side, trailer end of the ram car.

Among the agency’s recommendations in the best practices segment of the report was the use of proximity detection systems. In addition, officials stressed clear visibility, the use of transparent curtain in active face areas, and sounding audible warnings. Operation of lights in the direction of travel was also highlighted, along with personal strobe light use for all of those working inby the tailpiece.

At press time, a final investigative report of findings was pending.

MSHA’S FINAL FINDINGS

While all of the Q4 deaths are still being investigated, federal officials did release several final reports for past events during the time period.

One of those likely most anticipated was the results from a review of a May 12 coal rock outburst in West Virginia, the year’s only double fatality (which occurred at a mine targeted for its pattern of violations).

|

| MSHA released its final observations and conclusions in October from a May 2014 double fatality at Patriot Coal’s Brody No. 1 mine in West Virginia. It killed CM operator Eric Legg and roof bolter/MRS operator Gary Hensley. |

Continuous miner operator Eric Legg and roof bolter/MRS operator Gary Hensley were both killed while pulling pillars and extracting coal at the Patriot Coal’s Brody No. 1 mine in Boone County.

They were the fourth and fifth coal deaths of the year.

In its preliminary report, MSHA indicated the incident occurred at the No. 5 entry of the 4 East Mains panel. The room-and-pillar operation was of an average size, employing 193 with 171 underground.

In its fatalgram alert on the incident, the agency went on to say that crews were mining the second lift of the left pillar block at the time of the rib burst, and stressed the frequent and thorough examinations of mine roofs, faces and ribs in the wake of the incident. MSHA inspectors also highlighted the importance of following roof control plans and training all miners on the specifics of proper compliance to RCPs.

While retreat mining was not mentioned specifically in the agency’s best practices, officials did allude to mines’ need to ensure suitable pillar dimensions and mining method for a given area, and that roof and rib control is adequate for the depth of cover where work is being performed. MSHA also noted that a geological feature map should be developed, including unusual conditions, to determine the best mining plan to address potentially adverse roof and rib conditions.

In the final report released October 7, the agency did not indicate any discrepancies in training records for either worker, but did go into a lengthy discussion about a prior event on May 9 that was not reported to the mine’s district office — with similar circumstances without the more serious result. The operator was cited as a result, and MSHA did not close its books on the fatal incident without directly tying it in to its conclusion.

“The accident occurred because the mine operator failed to recognize areas with potential rib burst conditions, and to develop and implement a method of mining suitable to mine safely and control those conditions,” it reported.

“Mine management took insufficient actions to investigate the previous rib burst accident that occurred on the No. 1 Section on May 9, 2014, and failed to address hazardous conditions that caused the rib burst. Management’s failure to recognize and address the hazards associated with rib burst conditions, resulted in continued exposure to the hazard and led to the deaths of two miners on May 12.”

Closing out MSHA’s report was its root cause analysis, which confirmed that the operator subsequently abandoned the 4 East Mains section and discontinued retreat mining activities at the mine and discontinued all mining in the eastern side of the mine where the fatal accident occurred.

It cited Brody three separate times; the first was for a violation of 30 CFR, § 75.202(a), for rib support, again tied in to the unreported event.

“The operator failed to recognize a precursor burst, which occurred on the No. 1 Section on May 9, 2014, and also failed to take adequate corrective actions to protect the miners from hazardous rib conditions,” it said.

“The operator failed to develop and implement a plan, or method, of mining designed to eliminate the hazardous conditions associated with a coal burst, and at approximately 8:15 p.m. on Monday, May 12, 2014, a second violent burst occurred on the No. 1 Section fatally injuring two miners.”

A written notice of pattern of violations notice had previously been issued to the operator in October 2013, and officials also noted that the mine violated Standard 75.202(a) and was consequently cited 15 times in two years for the infraction.

It also was given a citation for a violation of 30 CFR, § 50.10(d), for not reporting the first incident.

“The operator failed to immediately report an accident…May 9, 2014,” MSHA said.

“This accident involved a coal rib outburst that covered the continuous mining machine operator with coal/rock debris from below his thigh, temporarily entrapping him and requiring assistance to free him from the rubble. Due to this accident, miners and equipment were required to be withdrawn from the active mining area in the Nos. 6, 7 and 8 entries.

“By not reporting this accident, the mine operator deprived MSHA the opportunity to investigate the accident and also failed to determine the root cause of the accident.”

Finally, a citation was issued for a violation of 30 CFR, § 50.12, as the mine did not properly preserve the accident site from the first of the two events.

“The operator allowed the destruction of evidence that would have contributed to the investigation of the accident,” the report noted.

“The failure to preserve this accident site prevented MSHA from performing an accident investigation into the cause or causes of the accident. The investigation would have prohibited mining activity in the affected area until MSHA permitted the operator to resume normal mining activities.”